Rumours of War

From Dubstep to Free Improv to Noise, people turn to music to express something about the world that words alone can’t. How well, then, do two recent books – Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare and the group work Noise & Capitalism – serve their listener-readers? A review by Paul Helliwell

In case of sonic attack on your district follow these rules…

- ‘Sonic Attack’, Hawkwind/ Michael Moorcock, sometime in the 1970s.i

‘The twenty-first century started with a bang’ says Steve Goodman (nearly) at the start of his 2010, MIT published Sonic Warfare. Taking us to the darkside of sound, Goodman focuses in on vibration, on a politics of frequency rather than volume, in particular the ‘bad vibes’ from the infrasonic bass frequencies of dub sound systems to those that engender fear and dread from military special weapons.ii He replaces the linear speed – a conjoined marker with the war and noise of the Italian Futurists at the start of the 20th century – with the angular velocity of afrofuturist music’s rhythmic vortices at the start of the 21st.century. Sonic Warfare moves an optimistic reading of Deleuze, based on flows, to one based on the vortex, ‘the model for the generation of rhythm out of noise [...] (that) blocks flow while accelerating it [...] the abstract model of the war machine.’ The vortex changes noise into rhythm, futurism into afrofuturism, and enables a hijack of the academic discourse on noise from within. But for Deleuze and Guattari ‘a war machine tends to be revolutionary, or artistic, much more so than military.’iii Why then does Goodman read it so literally?iv

War – What Is it Good For?

Music is joy. But there are times when it necessarily gives us a taste for death …music has a thirst for destruction

- Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 1980v

For an activity that so many people pin their hopes on, the philosophical position of music seldom rises above it being a distraction, and claims for its radical potential seem to be made more out of habit rather than real belief. As a weapon of war Goodman may believe he has found an example of sound working directly that cannot be ignored. If Deleuze’s philosophy is one of connection then Goodman uses it to draft the usual noise/war/speed suspects Arthur Kroker, Paul Virilio, Manuel DeLanda, Friedrich Kittler and many others into his own war machine.vi There is the omnipresent ecology of fear of the war against terror but also a militarisation of theory here; war – what is it good for? Kittler in tracing the roots of almost all media technologies to war would say that it is the father of all things, like the Italian futurists he must admit its value in shocking passeists, the ‘has beens’.vii As does Goodman, whose Sonic Warfare is both Deleuzian nomadic war machine and literal state war machine (this is a contradiction in Deleuzian terms but not an insurmountable one – the state may absorb the nomad war machine by capture).viii This gives the book a somewhat queasy affective tone – one too dark for music, but too flippant and celebratory for sonic warfare.

For Goodman these proliferating ‘Black Atlantean’ musics (dubstep, crunk, grime, baile funk, reggaeton, kwaito, hyphy) are a better fit to Deleuze and Guattari’s theories than the modern composition, literary, artistic, and B-Movie examples that litter their work, and more interesting than the Improv, guitars, and above all noise music that hog academic debate. In academia, music has been thought of in a number of ways, first it was understood (musicologically) in terms of the score, with black, popular and dance music discussed only as directly sociological documents largely in terms of lyrics, and only later did it come to be understood as sound. Goodman is still fighting this war against the lyric, and he acknowledges his formation in that Deleuzoguattarian swarm incubator the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) at Warwick University. Curiously, Goodman and the CCRU’s reliance on music’s (or noise, or rhythm’s) formal properties is little used by Deleuze and Guattari who are much more interested in its content ‘a child dies… a woman is born… a bird flies off’.ix Badiou dryly observes that Deleuzian concepts are often transported to another field only ‘to say that they function well’.x How has Goodman used Deleuze?

Wardance

One key CCRU debt would be to Erik Davis’s more than a decade old essay ‘Roots and Wires’, a reworking of John Miller Chernoff’s writing on African polyrhythm. This reading is the still present fossil-seed of the rhythmanalysis Goodman conducts. Erik Davis took Chernoff’s work on African polyrhythm and used it to provide a theory of the then current UK music jungle/ drum and bass in terms of Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition.xi When listened to, danced to, polyrhythm immanently appears as a steady metering beat (repetition), with a beat playing off it between these beats (difference). When composing or reading (viewed transcendentally) it appears as the interplay of a number of rhythms running in different time-signatures or perhaps at different metres (speeds). Rhythm here is an active relation of different regions, a productive tension. Crucially, what you take to be the metering beat can change – but no one dancing is going to thank you if you actually do this to them while DJ’ing. Repetition and metre are key in our collective mobilisations on the dance floor, in military drill, in the orchestra, in synchronising emotion, in synchronising labour – repetition and obvious, pulsed metre are the popular, the low, machine-produced prole-feed, and art music becomes itself by appearing to eschew them.xii Art reacts against the machines and views repetition as fatal and inhuman, we react with the machines, viewing the repetition they offer as cyclical and generous.

What Goodman is looking for here is perhaps not a theory of an already obsolescent musical style, but a means of connecting polyrhythm with Deleuze and Guattari. Surely, though, they should have commented on it themselves? He stumbles over his key problem in moving from the modern composition examples used by Deleuze and Guattari to other musics.xiii For Goodman the musical sources they draw on rule out a collective mobilisation. One example they use is Oliver Messiaen whom Goodman disparages for saying jazz and military marching are not rhythmic (but metered) and accuses him of being part of the ‘European musicological elite‘ (with Adorno – Ouch!), but a few lines later he must also acknowledge that Deleuze and Guattari say exactly the same thing. Goodman goes no further than to bemoan their snobbery, and then apply them as if nothing were the matter.

But perhaps Goodman is on more orthodox ground than he realises. In Messiaen’s music, elaborate strategies are adopted to produce a non-pulsed time – the Aion; for Deleuze and Guattari this is an elusive, fluctuating ‘time out of joint‘ in which new events may happen as opposed to the pulsed Chronos of steady metering historical time. In Deleuzoguattarian terms the time of the virtual is the Aion, its smooth space is of the nomadic war machine. But Deleuze has ignored the fact that metre is still relied upon by the musicians to produce an experience for the audience of non-pulsed time (how else could the musicians act together?).xiv The distance between Deleuze’s non-pulsed time and polyrhythm Goodman thinks unbridgeable, so he passes on quickly, but they may not be as far apart as he believes.xv

Rhythmanalysis

We have already seen the substitution of the vortices of a (black) afrofuturism for a linear speed of a (white) futurism, retaining the tropes of noise and war and a refusal of the original musical examples of Deleuze and Guattari. But Goodman also attempts a rhythmanalytic opening up of Deleuze and Guattari themselves, of their own influences/ connections (not Spinoza but Lefebvre, Bachelard, Bergson). Of the three inventors of rhythmanalysis acknowledged by Goodman, it at first looks as if Henri Lefebvre’s 1980 work will be marginalised in favour of an unpublished1931 manuscript by Pinheiros Dos Santos, but of the three Lefebvre is ultimately the most discussed. Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis arrived late in the Anglophone countries due to a 20 year gestation and a 28 year delay in translation. There is a further hangover – even Stuart Elden, in his translator’s introduction, cannot see Deleuze and Guatttari as adopters of Lefebvre’s technique, as if the writing on repetition and difference did not exist in both. To rephrase Lefebvre, is not a part of Deleuze and Guattari’s project a criticism of reification in the name of becoming, is it not taken up in what is most concrete; rhythm?xvi

This would be Goodman’s strongest argument – a way to overcome the view that (other than the refrain) Deleuze uses musical examples only as a metaphorical explanation of his arguments. Brian Massumi (the translator of A Thousand Plateaus) licenses us to make analogies from these when he enjoins us to treat that book as a record, as something that can be dipped into rather than read as a whole. In contrast Ian Buchanan and others argue we must build a properly Deleuzian theory of music – high or low – using Deleuze’s own tools.xvii

Life During Wartime

For me the smooth ride of Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant than the Sun (a sonic f(r)iction where musical example and Deleuzian text are in a state of mutual excitation) has not been achieved – the full torque Deleuzo-speak and the balancing statements required of academic writing don’t hold each other in constructive tension like the elements of a good polyrhythm ought to.

The book claims to be in a state of oscillation between ‘dense theorization’ and ‘exemplary episodes’ but none of these are from the author’s own experience as dubstep producer, record label manager and DJ, Kode9. He never intrudes upon his own text and there are no equivalents of the ornery Improv musicians who stifled Ben Watson’s monograph, Derek Bailey, in their emphasis on praxis. He takes us to a pirate radio station but don’t go expecting to meet the massive – it is as if the rapture has already happened. There’s no sweat, no sex, no dancing, no bodies, no violence, no records and little MC chatter. We are offered the rhythmic nexus but not the cash nexus. There is no testimony from the victims of sonic warfare either; most examples are internet rumour, urban (warfare) myths, Men Who Stare at Goats.xviii War here is remote, bloodless, simulated; war as we are increasingly offered it while our armies wage it at the peripheries – another training simulation of the Military Entertainment Complex.xix

Why this repression of example? When Melissa Bradshaw reviews Sonic Warfare in terms of Goodman’s recently released Hyperdub 5 compilation, he advises against it saying he is more interested in the inconsistencies and divergences between the book and the label.xx It’s not just the women who are missing from the book, she notes, it is humanity as a whole. She sees its being anti-anthropocentric as a good thing.xxi Having recently watched the UK reggae soundsystem film Babylon I cannot agree. Shorn of the people who improvise the combination of records and lyrics there is no understanding of the political economy of the soundsystem and why it has gone global. There is no understanding of these increasingly local scenes without recourse to the local and particular. Goodman has committed the cardinal Deleuzian sin of talking about communication rather than engaging in dialogue.

The book that Goodman meant to write, the one full of global Ghettotech, is announced in the forward and then banished to the footnotes, exiled by an editor as something that can only travel across the black Atlantic steerage. When, nearly at the end of the Sonic Warfare, Goodman enjoins us to ‘(listen) [...] for new weapons’ he also shies away from making ‘grand claims regarding the spontaneous politicality of the so-called emergent creativity of the multitude’ – this is the discussion he can no longer have with us because we are no longer there and neither is he.

The everyday is simultaneously the site of, the theatre for, and what is at stake in, a conflict between the great indestructible (cyclic) rhythms and the processes imposed by the socio-economic organisation of production, consumption, circulation and habitat… a bitter… dark struggle round time.

- Henri Lefebvre and Catherine Régulier.xxii

Noise in this World

Noise and Capitalism has the 11 authors’ experience built in (rather than designed out) – and after Sonic Warfare we might expect gains from this. Six of the authors I’ve met, two play free Improv, two play other kinds of music, Anthony Iles is a dubstep fan, Nina Power likes noise, Matthew Hyland reviewed the same copy of Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation that I did (and still has it), but then I’ve also met Steve Goodman (at the Noise Theory Noise conferences at Middlesex). Can these two books be brought into a productive tension?xxiii

First off the title, Noise and Capitalism, suggested by Ben Watson, (nearly) does what it says on the tin. The connection between noise and capitalism is the books problematic, it is a provocation designed to annoy the Wire, but the strengths of the essays on Improv pull the book in that direction. Are there problems in this doubling of improvisation and noise, last attempted in Jacques Attali’s Noise? – nothing happens without noise (says Attali) but little happens without improvisation (that is why the ‘work to rule’ is so effective). Both partake in the avant-garde fusion of art and life, one that, as Howard Slater argues, has become central to capitalism. Nonetheless before it can be compared to anything else, Noise and Capitalism must be brought into some kind of productive tension with itself. xxiv

If the free liberated without a doubt and in the poetic way in the 1960s, today it is only liberal.

- Free Improv’er Noël Akchoté

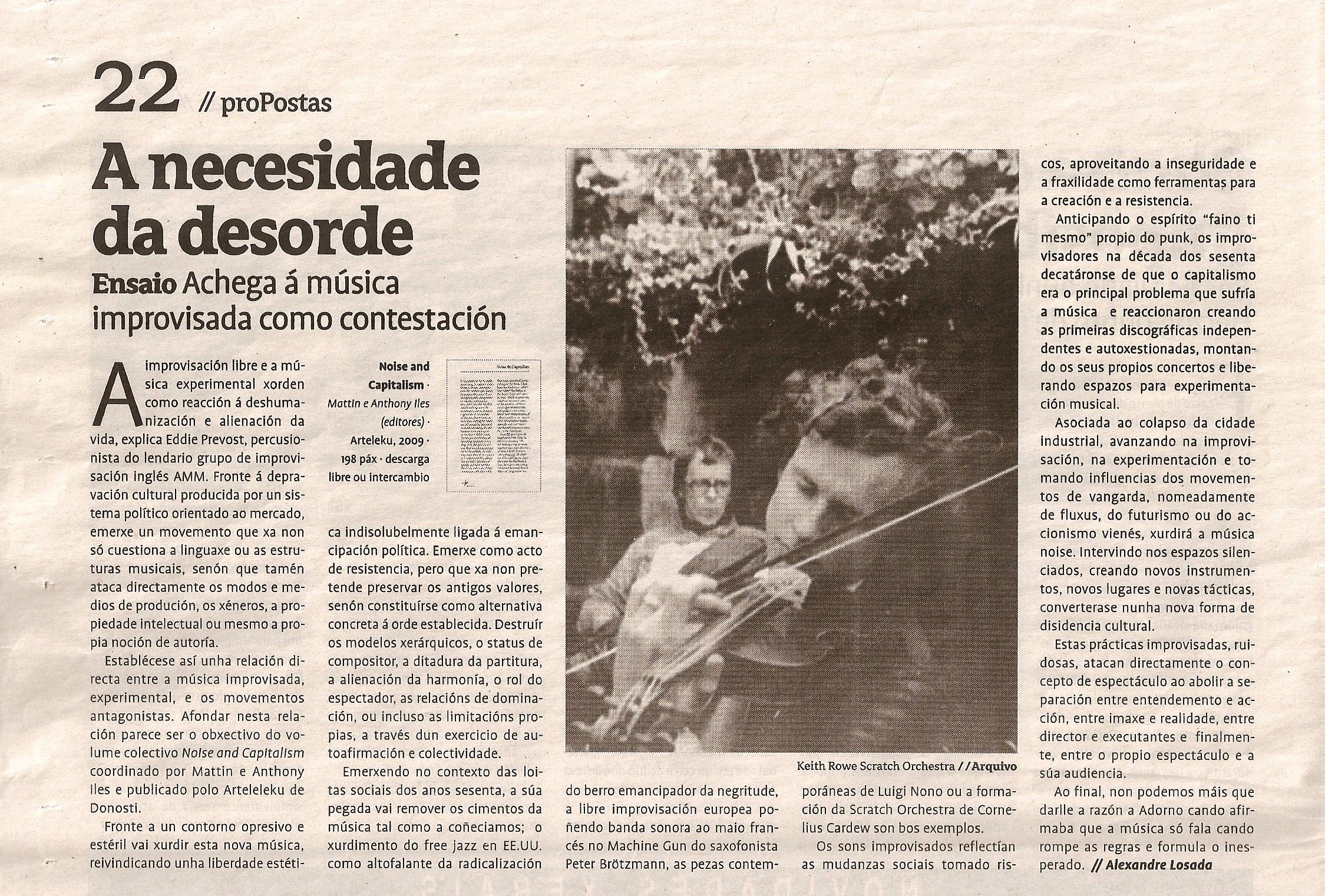

For Mathieu Saladin the Improv scene is composed of both Boltanski and Chiapello’s ‘social critics’, who are concerned with equality and denounce both exploitation and individualism, and ‘artist critics’ who resist the oppression of standardisation and commodification. If these currents were furthest apart in Dada and Italian Futurism, arguably the precursors of Improvisation and Noise, then May 1968 was the moment when these two were closest together. If the subsequent years have been marked by a recuperation of ‘artist criticism’ to the point where it has become ‘the new spirit of capitalism’, then ‘social criticism’ has also had its share of defeats.

Against this Saladin seeks, again, the improvisatory moment and Rancière’s degree zero gesture of ‘dissensus’ – that each work of art, or each such moment is a politico-aesthetic re-ordering of (not just) what can be said but (crucially) who can say it. The actually existing scene’s defects await new improvisers and a new audience to come. This separation of scene and practice, genre and concept that Mathieu makes is ahistorical, (and improviser Radu Malfatti is clear that without time/history we cannot assess stagnation or progression), but in holding them apart he at least makes the practice visible again.

But if the Improv was free, so now are the recordings. Mattin’s investigation of copyright and Myspace with Walter Benjamin’s Author as Producer in one hand and his Critique of Violence in the other leads him to a call for improvisation ‘changing the conditions in which the music is produced’ in such a way as to refuse the law (and violence) that guarantees copyright. In his interview with Radu Malfatti and a recent Mute article, Mattin reveals this would require the annihilation of Free Improv,

We are forced to question the material and social conditions that constitute the improvised moment – structures that usually validate improvisation as an established genre.

These genre conventions he now views as normalising strategies to be overcome, with Brechtian alienation technique, Improv to Impro. In many ways this is a working through of many of the critiques contained in this book.xxv Even the cover – notes of a dialogue between Her Noise exhibitor Emma Hedditch and Mattin as to what the cover should be – is made to do work, extending the dialogic of Free Improv outwards to make the process and critical thinking involved in the graphic design for the book visible.xxvi

Similarly, Matthew Hyland investigates Derek Bailey’s formation as a jobbing musician in the provincial dancehalls before the need to sound like the records put him out of work.xxvii Matthew notes that for musicians, once we were waged labourers and now we’re our own mini-brand with a career development loan, and this is the change in capitalism as a whole and for all of us (at least in the West). It is far from ‘idealism’, as Andrew McGettigan’s review in Radical Philosophy maintains, to question the centrality of the recording at the moment that capitalism dissolves it as a commodity, nor at the moment when it was being installed.xxviii

Howard Slater’s is perhaps the article that approaches Sonic Warfare most closely; his ‘War of the Membrane’ is about affect, but he is willing to venture into a discussion of capitalism and politicality in a way that Goodman is not. McGettigan bemoans this saying ‘It must make life more exciting to think that one’s listening habits are per se engaged in a war over instincts and perception’, but music is more than our individual listening habit, a fact obscured by its omnipresence. To dismiss music’s collective political (or psychoanalytical) effects as ‘a fantasy’ is a denial of what music is capable of. If it is a fantasy, it is a planet wide one. The problem here is in how Slater ends music, in a comfortable therapeutic silence no longer fear-filled ‘one day there will be no music, just possibilities’, but this is a return to the Aion.xxix

McGettigan recommends reading the essays by Prévost, Watson, Brassier and Saladin, and dismisses the rest. Prévost calls on us to resist scientism, authority and celebrity and to dive straight into the potent mix of self-assertion and collectivity that is Free Improv, one, he tells us, capitalism cannot acknowledge. Prévost is still fighting Stockhausen’s scientism, Cardew’s Maoism and Derek Bailey’s celebrity – faced with Messaien’s Aion he would twitch aside the curtain to reveal those musicians enslaved by the score. For Prévost, improvisation is an opportunity ‘to do rather than be done to’, a self-invention, something quintessentially human, about choice, and he has no time for its renunciation in Cage, Cardew or David Tudor’s preparation of an Aion-like mental state. But is there not something automatic and machinic in that moment of improvisation anyway, a randomness even of the notes that the tam-tam (Prévost’s instrument) produces when struck? Prévost looks to the work necessary to reincorporate this sound once made both musically (in the dialogue with other improvisers) and socially (in its relationship with the audience).

Ben Watson’s defence of the band Ascension against revisionist critical approval is in some ways a rerun of his Noise Violence Truth pamphlet – a defence of Noise. As a critic Watson has Adorno’s way with an aphorism (when not enjoined to Beckettian reticence by his negative dialectics), and yet when he soars with enthusiasm over the radical universal power of music he remains curiously unpunished by McGettigan.xxx

Brassier’s investigation of accumulating genre conventions in Noise doesn’t really do it for me (form is sedimented content – genre conventions change and grow, there is Noise within genres over time as well as between them). McGettigan thinks the editor should have teased out the difference in the concept of experience between Brassier and Watson – but I think it’s minor. For Brassier, Noise is over, ‘fatally freighted with neo-romantic clichés about the transformative power of aesthetic experience’, when the commodification of experience is ‘a concrete neurophysiological reality’ that cannot be defeated by criticism. But Brassier is good on what genre frustrates, even when it is hard to believe his musical examples can actually overcome it.

Anthony Iles, it seems to me, has done sterling work in his introduction pulling together the common problematics from these essays. Resisting the siren song of totalising theory, Iles pulls the argument down to street level, to the gentrification of Hoxton. If Improv is a muddy ditch where things can grow then so was Shoreditch (or at least the Foundry). Ultimately the proper engagement with these problematics is to be found in Mattin’s new work, but the decision by Kritika to make it freely available or available for trade both as a download and a physical copy is exemplary and performative.

Sadly Nina Power and Csaba Toth’s articles are little more than well referenced reviews, but interesting nonetheless. Csaba dutifully references Attali, Barthes, Lacan (and the less-usual Guy Debord) in constructing his ‘Noise Theory’. He follows Barthes (via Jeremy Gilbert), finding the radical potential of Noise in jouissance which, like the improvisatory moment, is a moment that overcomes everything – it is a black hole, an aesthetic sovereignty in reduced circumstances, a fetish of the moment. Does Noise music really have that effect on people listening to it five times a week? There is no ‘going fragile’ here – no admission that music or noise or even theorising them can fail. As with Sonic Warfare, the maximalist claims for the direct effect of sound derive from the philosophical weakness of generalised claims of music.

Nina Power offers us machines dreaming of the deft hands of women workers, women building synthesizers, wartime women rebuilding Waterloo Bridge – taking as her cue a comment of Mattin’s that factory workers were among the earliest players of Noise. Countering her appreciation of musician and synthesizer maker, Jessica Rylan (surely just a peg for the article?), McGettigan lists radiophonic women but omits the mother of them all Daphne Oram. ‘The sirens of unpleasantness continue to seduce the male noise imaginary’, says Nina, hearing these as merely imitative rather than annunciatory, you’ve been in the house too long she says and shoos us out into the fresh air.

Soundclash – The Philosophy of Improvisation Or…

McGettigan’s review is also a double review and, if not that helpful for Noise and Capitalism, it did help me with the review for Sonic Warfare. It starts by reviewing Gary Peter’s The Philosophy of Improvisation, one improvised a half page at a time.xxxi McGettigan seems resistant to philosophical improvisation – what about Alain’s Propos? -but what really gets his goat is the failure to cite musical examples (and the idea that a philosophy of improvisation has little to offer improvisers).xxxii I have a similar problem with Sonic Warfare, the obverse of my usual problem that too much faith is placed in musical example; musical examples date fast (Goodman’s problem), and if I don’t like the music I’m less likely to be convinced by the argument. Even if I do, it may not be for the reasons given. The mutual excitation of text and music – the sonic f(r)iction – crashes on take-off.

McGettigan argues that, because Gary Peter’s book gives no concrete examples, no philosophy of the practice of improvisation can be generated, and a model of abstract aesthetic production is imported in its place. He then turns to Noise and Capitalism as a native informant to find accounts of practice that would enable him to generate such a philosophy, but finds people already busy theorising (and sometimes importing). McGettigan’s disappointment is palpable, and he focuses it on the lack of consistency between these accounts. This is right but not, as he seems to think, because more consistency would produce a truer argument but because it is this lack of consistency that interests – other reviewers also found the lack of agreement frustrating – but I find it heartening.xxxiii

The conflation of the genres Noise and Improv by the book’s compilers and McGettigan is productive, but just because they can sound the same doesn’t mean they are. The conflation of their concepts, objects and eventual aims, hides more than it reveals. Similarly the conflation of the genres of Noise and Industrial hides their differences (the demolished factories, the changes in work).

Musicologist Susan McClary once complained that to understand music we are told we must renounce our emotional reactions to it, refusing to do this she picked Attali over Adorno, and for the same reasons Ronald Bogue picked Deleuze. McClary also made her choice to route round what she took to be Adorno’s high culture bias – just as Goodman picked Erik Davis.xxxiv The repetition of these gestures surely says something.

These two books do not allow us instantaneous access to the truth of all noise but to theoretical and practical conjunctures – problems of the relations between philosophy and practice. McGettigan may complain that the referencing is scholastic ‘if Adorno says it, it must be true’ to the point of denial of experience, but the same is true of Sonic Warfare. A whole cultural studies industry exists solely to publish ‘neat ideas’ shorn of their philosophical ‘procedures’ for use by undergraduates wanting to write about what excites them. Beyond this, the whole thrust of the work of Derrida, Deleuze and Rancière is to question what it is these procedures do – philosophy is not some neutral activity. It is not enough to reclaim praxis as a mere term or to police the borders of philosophy with a bigger dog. The problem of theorising why music matters so much to so many people, and of not having to renounce emotion to do it, remains philosophy’s problem, not music’s. Music continues to move the crowd.

Paul Helliwell <phelliwell2000 AT yahoo.co.uk> does not improvise but does record and would like to direct people to his blog on the myspace page of his ‘brother ass’ horsemouth: http://www.myspace.com/horsemouthfolk

Info

Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear, MIT, 2009

Mattin & Anthony Iles eds., Noise & Capitalism, Arteleku Audiolab (Kritika series), 2009

i http://youtube.com/watch?v=LwRvWpsiM2w

ii See http://weirdvibrations.com/2010/02/04/review-3-sonic-ecologies/ for an attempt to set up a politics of noise/ politics of silence ‘quarrel of carnival with lent’ against which Goodman posits a sonic ecology.

iii Gilles Deleuze, Pourparlers, Editions de Minuit 1990, pp.50-1.

iv For a succinct discussion of the concept of the ‘war machine’ see:http://www.capitalismandschizophrenia.org/index.php?title=War_machine

v Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, Athlone Press, London 1992, p.299.

vi And a whole series of books proclaims that it is, not just John Rajchman, The Deleuze Connections, MIT 2000.

vii The best criticism of this was probably made on 15 July 1917 by mutinous Italian squadies of the Cantanzaro Brigade who machine-gunned the inn where proto-futurist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio was believed to be staying. John Woodhouse, Gabriele D’Annunzio, OUP, p.306.

viii Deleuze and Guattari, Op. cit., plateau 12, 1227: ‘Treatise on Nomadology – The War Machine’, p.351- 423 and elsewhere.

ix Ian Buchanan, ‘Introduction’, in eds., Ian Buchanan and Marcel Swidoba, Deleuze and Music, Edinburgh University Press, 2004, p.15.

x In Jean Godefroy Bidima, ‘Music and the Socio-Historical Real: Rhythm, Series and Critique in Deleuze and O.Revault d’Allonnes’, in Ian Buchanan and Marcel Swidoba, Op. cit., p.192-3.

xi Erik Davis, Roots and Wires, http://.levity.com/figment/cyberconf.html But are jungle records (composed on computers, out of loops, programmed on a grid to a fixed tempo) really polyrhythmic in the sense of African drumming? Perhaps when danced to, perhaps when listened to, perhaps when mixed together, but not of themselves.

xii See William H. McNeill, Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History, Harvard University Press, 1995.

xiii Jeremy Gilbert notes ‘when writing about music they almost invariably write about composers‘ Jeremy Gilbert, ‘Becoming Music: The Rhizomatic Moment of Improvisation’, in Ian Buchanan and Marcel Swidoba, Op. cit., p.121, and ‘from the vantage of the artist rather than the audience’ Ronald Bogue, Deleuze on Music, Painting and the Arts, Routledge, 2003, p.3. But is this true? – surely what Deleuze focuses on is the experience of music (its affect) rather than its production.

xiv In the ‘does-what -it says-on-the tin’ Quartet for the End of Time, a 17 beat musical phrase is repeated against a 29 beat chord pattern, the shifting relationship between the two refuses to settle down and as these are both prime numbers the earliest that the piece can begin to repeat itself is 17 times 29 beats later. At last music you can play at a rave and not be busted by the cops under the Criminal Justice Act. Ronald Bogue, ibid., p.14 onwards. Quartet for the End of Time is another technology produced by war having been written by Messiaen in a German prisoner of war camp.

xv In Deleuzian terms, pulsed, polyrhythm cannot produce the Aion, it produces a striated space rather than the smooth space of the nomad war machine. Lefebvre however notes another kind of time. People may be distressing themselves unnecessarily about repetition.

xvi Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis, translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore, Continuum 2004, p.7.

xvii Translator’s forward; pleasures of philosophy, Brian Massumi, p.xiii, in A Thousand Plateaus, Op. cit., We might start from scratch and apply Deleuze’s 6 key concepts to music itself, applying them according to low music’s own immanent terms, or we might think about music in terms of Deleuze’s work on cinema, or we might think about music in Deleuze’s terms of royal and minority science (or minority languages), or we might (in an UN-Deleuzian fashion) attempt to dialectically wrangle music out of him with the aid of another philosopher. Arguments made by (in order) Ian Buchanan, ‘Introduction’ , Greg Hinge, Is Pop Music?, Drew Hemment, ‘Affect and Individuation in Popular Electronic Music’, Eugene Holland, ‘Studies in Applied Nomadology’, Nick Nesbitt, ‘Deleuze, Adorno and Musical Multiplicity’, Jean Godefroy Bidima calls for both of these last two in , Music and the Socio-Historical Real: Rhythm, Series and Critique in Deleuze and O.Revault d’Allonnes. Bidim points out that Deleuze is, by his own philosophy, required to make those connections beyond himself but did not and compares Deleuze unfavourably with his college friend Revault d’Allonnnes who made studies of rebetiko and other minority musics. This should keep Matthew Hyland happy as he plays a variety of rebetiko with his band Philosophie Queen. All in eds. Ian Buchanan and Marcel Swidoba, Op. cit..

xviii Interestingly Steve Goodman’s Blog does all this much better, http://sonicwarfare.wordpress.com/

xix http://speechification.com/2010/03/17/robo-wars/ and http://speechification.com/2010/03/02/from-gameboy-to-armageddon/

xx http://sonicwarfare.wordpress.com/ 10th January 2010.

xxi It follows a tendency begun in Deleuze and continued in More Brilliant than the Sun, where Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic, a study of real transatlantic patterns of affiliation and connection in Black Culture, is sunk beneath the waves to become a Black Atlantis rendered myth.

xxii Henri Lefebvre and Catherine Régulier, ‘The Rhythmanalytical Project’ in Rhythmanalysis, translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore, continuum 2004, p.73.

xxiiiThis would not be the first double review of the book see http://weirdvibrations.com/2010/02/04/review-3-sonic-ecologies/ for an attempt to set up a politics of noise/ politics of silence quarrel of carnival with lent against which Goodman posits a sonic ecology.

xxiv Improv is prefigured in Dadaist and Surrealist automatism. There was little to separate futurist and Dadaist performance as practice but a great deal separating them as ideology (War or anti-War) See Michael Kirby, Futurist Performance, Dutton, New York 1971 and Richard Huelsenbeck Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, University of California Press, Berkeley 1991.

xxv See his recent article http://metamute.org/en/content/against_representation_a_of_representation_in_front_you and Keith Johnstone, Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre, Routledge, New York, 1992. While keen to avoid involving us in the unpaid labour that is relational aesthetics (so happy together) isn’t this production of a problematised situation (sociability as blockage) potentially similar to the work of Santiago Sierra.

xxvi http://hernoise.blogspot.com/ and http://e-flux.com/shows/view/3746

xxvii It was there Bailey acquired the muscle memory to ‘bodge’ songs he had not learnt previously nor had access to the sheet music for, which together with his studies of atonal musics were the underpinning of his ability to improvise.

xxviii Andrew McGettigan, Begin the Beguine, in Radical Philosophy, Issue 160, March/April 2010, p.46-49.

xxix And curiously similar to the self-communication of Attali’s idea of ‘composition’.

xxx Like Nick Nesbitt in Deleuze and Music he wants to convince us that Adorno would have dug John Coltrane but I don’t see any evidence for that. Noise Violence Truth text available online at http://andyw.com/publications/music_violence_truth/

xxxi In McGettigan’s account this is a pseudo-(Derridean) philosophy because it has not taken account of Derrida’s hostility to using ‘origin’ to determine the ‘proper’ (I may be misunderstanding something here).

xxxii http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89mile_Chartier

xxxiii http://arteleku.net/noise_capitalism/ has the reviews plus some of the work traded for copies of the book.

xxxiv Ronald Bogue, ‘Rhizomusicosmology’, Substance 66, University of Wisconsin, 1991, p65-101. http://www.scribd.com/doc/23289005/Rhizomusicosmology-Author-s-Ronald-Bogue-Source-SubStance-Vol-20-No-3

, a contemporary art center in Donostia-San Sebastián, the capital of the province of Gipuzkoa, in the Basque Country, Spain.

, a contemporary art center in Donostia-San Sebastián, the capital of the province of Gipuzkoa, in the Basque Country, Spain. at the Arteleku’s website. Writing this blog-entry moreover should earn me a paper copy of the book. Interesting idea, to let reviewers have a physical copy only after their review has been published

at the Arteleku’s website. Writing this blog-entry moreover should earn me a paper copy of the book. Interesting idea, to let reviewers have a physical copy only after their review has been published ![]() … Arteleku offers an even more general possibility for exchange. Indeed, anyone engaged in some sort of artistic activity, is invited to send a sample of her/his work to Arteleku and get a hard copy of the book in return. The material sent will become part of Arteleku’s public library.

… Arteleku offers an even more general possibility for exchange. Indeed, anyone engaged in some sort of artistic activity, is invited to send a sample of her/his work to Arteleku and get a hard copy of the book in return. The material sent will become part of Arteleku’s public library. ‘s contribution Noise as Permanent Revolution or, Why Culture is a Sow Which Devours its Own Farrow to be one of the better reads in the book. He observes that the sometime experience of ‘noise music’ as an ‘unflinching barrage’ [...] has more in common with Beethoven’s Große Fuge

‘s contribution Noise as Permanent Revolution or, Why Culture is a Sow Which Devours its Own Farrow to be one of the better reads in the book. He observes that the sometime experience of ‘noise music’ as an ‘unflinching barrage’ [...] has more in common with Beethoven’s Große Fuge (1825) than it has with many of the more obvious and contemporary references. Ben also points out that a whole lot of the ‘noise’ indeed is little more than sonic wallpaper, a safe & trendy pose of ‘subversion’, devoid of merit or interest.

(1825) than it has with many of the more obvious and contemporary references. Ben also points out that a whole lot of the ‘noise’ indeed is little more than sonic wallpaper, a safe & trendy pose of ‘subversion’, devoid of merit or interest. (seminal to the development of free improvisation as a practice), whose earlier writings on the subject are extensively cited by some of the other contributing essayists, and who himself contributed an article entitled Free Improvisation in Music and Capitalism: Resisting Authority and the Cults of Scientism and Celebrity. Edwin points out that in some sense the musics under consideration exist precisely because of the socio-economic strictures of a capitalist culture (italics are mine). Moreover, as French musician and researcher Matthieu Saladin points out in his paper, Points of Resistance and Criticism in Free Improvisation: Remarks on a Musical Practice and Some Economic Transformations, the profound mutations carried out by capitalism from the second half of the 1970s (which allowed its redeployment in the following decade) seem to have mainly been brought about by employers’ organizations taking into consideration the demands [for more freedom and individual autonomy] that stemmed from artistic criticism[, refusing] control by hierarchy and the planning of tasks.

(seminal to the development of free improvisation as a practice), whose earlier writings on the subject are extensively cited by some of the other contributing essayists, and who himself contributed an article entitled Free Improvisation in Music and Capitalism: Resisting Authority and the Cults of Scientism and Celebrity. Edwin points out that in some sense the musics under consideration exist precisely because of the socio-economic strictures of a capitalist culture (italics are mine). Moreover, as French musician and researcher Matthieu Saladin points out in his paper, Points of Resistance and Criticism in Free Improvisation: Remarks on a Musical Practice and Some Economic Transformations, the profound mutations carried out by capitalism from the second half of the 1970s (which allowed its redeployment in the following decade) seem to have mainly been brought about by employers’ organizations taking into consideration the demands [for more freedom and individual autonomy] that stemmed from artistic criticism[, refusing] control by hierarchy and the planning of tasks. (moniker of Oscar Martin) that has appeared as the 15th release in the Free Software Series

(moniker of Oscar Martin) that has appeared as the 15th release in the Free Software Series , promoting experimental works that were realized using

, promoting experimental works that were realized using  free software

free software .

.

on the furthernoise website, Derek Morton provides a detailed log of his personal listening journey. Here is my rendition of Derek’s impressions:

on the furthernoise website, Derek Morton provides a detailed log of his personal listening journey. Here is my rendition of Derek’s impressions:)]